nota bene: all images are reproduced for research purposes, all rights reserved to their authors.

P A N O R A M I C O

1968 built by Chaves da Costa, initial project by Franciso Keil do Amaral

wallpainting: Luis Dourdil

ceramics: Manuela Madureira

mosaics: Querubim Lapa

Presence

- one striking question arising while being inside or in the proximity of the Panoramico is its presence: the nature of its monumental but inclusive agency, in which it contains the visitor and merges with the surrounding landscape.

Thinking that the Panoramico was designed as an exclusive site, inscribing strict socio-geographical delimitations, one can ask in which way did its agency mutate with its progressive ruination.

- the Swiss architect Peter Zumthor talks about architecture's mission to 'produce presence' in his various books. At the same time he warns against the political instrumentalization of aesthetic presence of architecture.

- In order to consciously work with the presence of built form, Zumthor started to build 'houses without form', in which ideologically charged forms would be avoided. His house designs with no plans, sections or models were projected with the intention to construct an effect upon the viewer which would project alternative life concepts. (Peter Zumthor, Thinking Architekture, Birkhäuser, 2003);

-Thinking back to the Panoramico it becomes interesting to observe the measure in which the projected building (the fascist ruling class' restaurant) started to produce new and always changing spatial and material forms – once it progressively lost form and decomposed. With these newly emerging spaces, the site's presence shifts, which in its turn shapes new social situations, new ideas of social use and formulates 'alternatives' to the surrounding socio-political environment (the place changing rapidly its functions and finally becoming a site for the socially excluded). A multiple architectural 'presence' – closer to the monumentality of natural growth, than to that of a designed environment – develops progressively.

Model

- Situated on the hill above the urban agglomeration as a point of observation (protected by the artificial forest planted in the 1930's also during the regime of Salazar), it was also supposed to function as a visual symbol of power – to which one 'looks up'. Being in fact only sporadically integrated into the urban lived reality and therefor changing constantly its functions, it could be seen as a model in real scale.

The Panoramico functions as a model – since models represent a condition that is unattainable, they materialize aspects that reality cannot accomplish. Although a model intends to closely follow the possibilities of the real, it overpasses these possibilities therefor fails to fully materialize. In the case of the Panoramico there is always a gap between what it was destined for and its actual material form, its social use and its 'presence'. Like Ian's video reveals, a model that seems to be formally complete and finite, is actually unfinished, broken in relation to reality – the gap between reality and the representation of its possibilities.

Panoramico as model – also because it is rather a contemplative environment now: it is less functional, and it is more an object of contemplation.

Ruin

- The Panoramico demonstrates the dysfunctionality and un-appropriatedness of certain architectural functions in the economy of the city. On the other hand, as any ruin, it shows the intrinsic capacity of transformation of built matter. It shows how a ruin is the result of an autonomous life of any built form – in relation to its environment. The building itself develops other functions, as well as other material and aesthetic forms than the ones prospected for it in the 'model' stage. In this sense we can think about an anarchic potential of any built form – which is confirmed by the restaurant's alternative social uses, which took over the projected functions of the building.

Ruin vs. model

Ruin and Model as two architectural forms seem to belong to different temporal moments on the timeline of a building: the model is prospective (intended to differentiate formally and functionally), the ruin is regressive (intended to efface differentiation). Nevertheless in the case of Panoramico, these two forms seem to meet. The restaurant occupies a median position that condenses simultaneously these two temporal and spatial moments: the building has traversed in time various prospective and exclusive functions (from high-class restaurant, to disco, bingo, warehouse, hiding place and abandoned site) which were not integrated into the urban fluxus and didn't last. The building nevertheless ended up successively effacing its prospective functions and their differentiations.

A model, programmed for a future time, could be seen as a monument of the 'real'. On the contrary, a ruin is a 'virtual' monument – it describes a constant negotiation and surpassing of the possibilities that a built form could manifest in reality.

In its present form, Panoramico exhibits a multiplicity that is not present in a model (which is usually oriented towards a single vision). The restaurant's heterogeneity and diversification are rather forms developed by ruins (like in Ian's video where 'model' and 'ruin', as well as 'object' and 'environment' are fused).

The building modifies and directs the user's reactions due to the fact that it fuses spatial forms, nature and build form and functions and becomes more and more un-inhabitable. As the building decomposes and develops more anarchic forms, it also reaches a higher level of abstraction: the viewer approaches the Panoramico rather as an art object, involuntary installation/aesthetic/natural environment, than as architecture.

The progressive ruination of the architecture and the recent decision of the city of Lisbon to turn the Panoramico into an official viewpoint, is a fortunate solution and a logical outcome of its natural development. Once excluded from the social context (a model doesn't include the social context the building is meant for, but remains isolated), it turned into a ruin that connected the building back to its social context (through illegal, clandestine visits and anarchic acts). After an official evaluation that its refurbishing would cost 20 millions, the city council was forced to bring it back into public use as an 'official' viewpoint – involuntarily legalizing its informal, naturally developed use.

Monument

monuments are built with the intention to symbolically incarnate certain values, but as they witness change and transformation they end up expressing not only aspirations, but also failures and nostalgias, missed speculations about the possibilities of the real. Like institutions, monuments have a coercive function.

But contrary to a 'classical' monument, which is supposed to conserve and exhibit historic information, the Panoramico in its current state camouflages the information that it has accumulated in time. Taking an autonomous course of transformation, the building stopped communicating a pre-defined message to the urban context.

In the early '90s James Young launched the concept of the Counter-monuments – memorial spaces conceived to challenge the very premises of their being. (James Young, The Counter-Monument: memory Against Itself in Germany Today, in Critical Inquiry Journal, vol 18, No.2, Winter 1992). 'The aim of the counter-monument is not to console but to provoke, not to remain fixed but to change, not to be everlasting but to disappear, not to be ignored by its passers-by but to demand interaction, not to remain pristine, but to invite its own violation and desecration, not to accept graciously the burden of memory, but to throw it back at the town's feet.' (pg. 277)

Young writes about self-consuming sculptures (naming the works of Jochen Gerz, Jean Tinguely among others) and which are leaving behind only a memory of themselves in the viewer's eyes. Young asks himself which are the specific reasons for the vanishing of each of these self-consuming monuments. (pg.278). Some of these reasons are for him: escaping the commodification system, being entirely integrated into the public (the viewer becoming the work), exhibiting their own failure and preventing the artificial remembering instead, promoting the internalization of the lessons of history. Young cites Jochen Gerz, who talks about monuments as 'invisible pictures', locked into the mind as perpetual monuments (pg.278). The best monument in Gerz's view is the memory of an absent monument.

Thinking about the possibility of an anti-fascist monument, Young talks about one counter-monument that would not only commemorate but mostly enact, breaking down the hierarchical relationship between art object and audience. This monument undermines its own authority by incorporating the authority of its passers by. (pg. 279)

'The counter-monument is dissipating itself over time, it would become more like time, than like memory. It would remind us that the very notion of linear time assumes memory of a past moment. The counter-monument asks us to recognize that time and memory are interdependent, in dialectical flux (pg. 294). In its conceptual self-destruction, the counter-monument refers not only to its own physical impermanence, but also to the contingency of all meaning and memory. Young identifies the beauty of the counter-monument (among others) in its capacity of change and in its capacity to challenge a society's reasons for memory.

Institution

The Panoramico can be seen as a muzeified institution, or a museum preserving future institutional forms, where naturally occurring experiments and events enact the future of decaying and forgotten establishments. The accumulated debris permanently on view in the Panoramico (including perpetually braking fragments and external detritus coming in with occasional users) exhibits the inherent self-consuming destiny of any institution. The buildings enacts panoramically precisely the process of fossilization of an establishment projected for consume.

Similarly, the former Eastern Europe is still populated by ghost monuments impersonating a 'future perspective' of once immutable coercive institutions: from fallen statues of Stalin and Lenin marking the landscape to monstrous constructions like the Hoxha pyramid in Tirana. The likewise circular building, the Hoxha pyramid is reproducing a universal iconography of domination and was built in 1988 as a mausoleum of the dictator Envers Hodja by his architect daughter Pranvera Hoxha. Following the fall of the communist regime in 1991, the building was reconverted into conference center, disco, hiding place of an the OTAN grouping during the Kosovo war and became finally the platform for protestatary meetings and violent demonstrations against the actual regime in Albania.

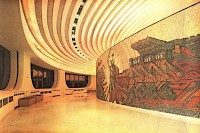

Architecturally similar to the Panoramico is also the Memorial House of the Bulgarian Communist Party on mount Buzludzha, designed by the architect Georgi Stoilov. More than 60 Bulgarian artists collaborated on the design of murals for the site, and thousands of forced labourers were involved in the construction process, which took seven years to complete. The memorial house was officially opened in 1981 by the Bulgarian Communist regime to mark the centenary of the Socialist movements - a predecessor of the Bulgarian Communist Party. After the fall of the Communist regime in 1989, the building is now officially closed to the public, abandoned and vandalised.

In-numerous projects have been devoted to the documentation of these communists spectral presences and revealing in fact the fortunate hermeticism of these buildings, which progressively bring into putrefaction their corrupted information and render unintelligible the traumas of the past.

In fact it seems that the more presence they gain, institutions and museums imperceptibly and gradually eliminate the material and informational vestiges of human agency and their architectonic residues and as Zumthor affirms, become 'houses without form'.