My paper is dedicated to images that the contemporary artist of Angolan origin now living in Lisbon Delio Jasse shot in Luanda, with modernist architecture built in the decades between 1950 and 1975. I will focus on the phenomenon of so/called 'late modernity' that marked the last decades of colonial rule in ANGOLA. I will extract the political potential of Jasse's images which is based not on a polemic statement but goes back to techniques of documentation that Jasse elaborates.

Therefor I will briefly map the cultural context of the epoch and compare various types of documentary photography shot with these same buildings ~ landmarks of late colonial architecture ~ shot in various epochs and with a different intentions.

A great collection of archival images and texts, documentary material dedicated to these buildings erected during the Estado Novo, can be consulted on this research website: HYPERLINK "

/"ignored modernity. Besides being shot in different epochs (with their specific aesthetic and technical determinations), I asked myself what is the difference between the type of documentation that Jasse's images and these genuine documentations practice?

The modernist, or so-called 'rationalist' architecture in Luanda Angola developed in the framework of colonialist urbanistic plans. It was usually designed from Lisbon during the Estado Novo regime (the dictate of Antonio de Oliveira Salazar in Portugal) by architects which were working for the Ministry of Colonies (which was later called Ministerio do Ultramar – The ministry of the Overseas). Nevertheless this architecture took its own course, that quoted the International Style and the Brazilian modernism. Many examples of this particular style are still standing in the ex-colonised countries: an adaptation of modernism tuned to the climacteric and social local necessities. Most of them are presently in a state of decay, destroyed by lack of maintenance and a succession of wars, after the liberation from the Portuguese.

A notorious example is the Grande Hotel of the city of Beira in Mosambique, constructed by the Portuguese architect Francisco Castro. Modern Beira was projected on paper by Jose Porto e Ribeiro Alegre and the urbanistic plan was approved in 1947 in Lisbon. As it was stated in the official project, the city was imagined as a melting pot for all races, in the situation in which they had European habits. Today, the Hotel seems a mutated being, mocking the striving for permanency with which it was designed: populated by hundreds of families, occupying the various rooms, the hotel accommodates now the immediate needs of the daily life. The functions of its architectural elements have been readapted, overbuilt with temporary materials, elements removed and transformed.

A similar example, this time from Guinea Bissau, is the Palace of the Government in Bissau. It was built by the Portuguese architects João António Aguiar e José Manuel Zilhão in 1945, who tried out a new, more appropriate style for the colonies, but still without renouncing the canon of 'traditional' Portuguese architecture. The building was bombed in 1998, was abandoned and has been recently restored by a team of Chinese architects and engineers – a phenomenon currently common in many African countries.

In an erudite article, Ignored Modernity: The case of Luanda, Paula Nascimento makes a brief history of the Angolan 'late modernity' and its political background, focusing on Luanda. After the big coffee boom in the early 1950s and an increasing industrial development, which brought an enhanced investment, the city started to grow without building regulations, which augmented the differences between the center and the uncontrolled spreading of its outskirts. Paula Nascimento explains that during the Estado Novo, Angola was on one hand subjected to the repressive state authority, on the other hand, being at distance from the ruling center, it gained a zone of liberty. In architectural terms, this was the opportunity to break the ideological constraints designed in Lisbon and turn towards an international style and to Brazilian models (more adaptable due to the tropical similar conditions). In this way Angola became a platform for experimentation in architecture, both on a formal and an ideological level.

The main outcomes of this phenomenon were:

Firstly the attempt of democratization of the urban space, by integrating the presence of lower class citizen into the urban fabric.

Secondly: irregular aarchitecturaal structures that reflect local popular architecture.

The Angolan born architect Fernao Simões de Carvalho (who had worked under le Corbusier), reintroduced irregular traditional structures and integrated suburbs, while Vieira da Costa projected around 1950 the socially responsive market of Kinaxixi, recently crashed, abandoned and demolished. In an interview, Simoes de Carvalho talks about the different solutions that he developed in Luanda face to climatic requirements, which brought a distance from the ideological charge that contemporary buildings carried in Lisbon: the sun parapets, the balcony and terraces, the openness of the facades. Ana Vaz Milheiro identifies these elements as being specific for Portuguese colonial architecture in general: a classic composition (characterized by monumentality, hieratism and often a threefold structure) together with devices for sun protection and inventive ventilation systems.

Thirdly: architecture as a means to promote social integration

Simões de Carvalho and other active architects in this late colonial period intended to end the separation between Angolan and European neighbourhoods. Simões de Carvalho had been a student of Le Corbusier. He designed in Luanda a sort of Unite d' Habitation menat to integrate locals with Europeans. This complex of buildings was never finished.

De Cravalho and Vieira da Costa created a style that in a way negated the principles of modernism themselves: “sterile, standard, international”. They understood architecture as a result of the social and ecological environment in Luanda to which they adapted formalist principles. The Kinaxixi market build by Vieira da Costa was an architectural structure emerging from the traditional African way of life.

This building and the so~called Cuca building (built by Luís Taquelím da Silva and situated on the Kinaxixi square), are constantly appearing in all types of documentary photograpphy of Luanda. They have been considered paradigmatic for this 'late colonial' architecture and their fate has been seen as part of the cultural Angolan identity. They receive this symbolic meaning also in the images of Delio Jasse. Together with the buildings around, they both have progressively degradated, as a consequence of the decay brought by a row of wars: the Angolan War of Independence, followed by almost 20 years of civil war, in which very little was built. They housed underground activities in their ruins, and were finally abandoned and demolished in 2008 and 2010.

The demolition of the CUCA building, gave way to debates regarding the notion of urban modernity, as connected to the colonial past. It caused protests from academics and inhabitants of the city which had pleaded for restoring of these historic buildings instead of selling the terrain to new investors.

Looking at documentary representations of Luanda, the central functions of CUCA and the market of Kinaxixi become obvious. Their phantom presence in the collective memory questions in which degree the contemporary urban lifestyle deviated from this 'projected modernity' and if their fall was not a direct consequence of that.

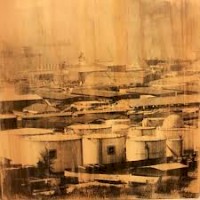

In recent street view photos, most of these buildings risen in the period between 1950 to 1975 appear severely run down, with facades that had never received a finish, sinking under the weight of use, painted sporadically or patch-work tiled, with balconies carved-in or bricked off, with clothes hanging to dry, with windows build of improvised materials, with parabolic antennas and added tin roofs. Besides showing precariousness and a contingent way to live, these details of present daily life, integrate an informal dimension to the aspired formalism of the architectural style, but make also a counter-statement to the photographic documents of the epoch, in which use had not yet installed and the formal purity of the 'modernist style' was played out.

The images of Delio Jasse occupy a completely different position in this range of documentary photography. They catch the enduring formal classicism of the architectural vocabulary of these buildings, to which they confer the importance they have in the cultural landscape in Angola (with their acknowledged architectural weight and their catalysing cultural role). At the same time, Delio Jasse's photos transport also a more fictional information, which brings us back to the character of these buildings, as both prospective and regressive. These accurately documented architectural forms, glide between their projected past that was never materialised into a 'modernist' future and a lived present that carries the reality of these unaccomplished plans.

It is precisely in this aspect of 'reality' taking over the utopia of modernism, that Paula Nascimento recognises the value of these hybrid neighbourhoods: a 'morphing space' in which a mix between the centre and the periphery, the formal and the informal way of life is for the first time possible and generated by architecture.

I would like to argue that the way Delio Jasse's works with documentation, is producing the critical statements of his images. In this sense I will point out the particularities of his way to conceive documentation.

Firstly: Contrary to documentary photography that freezes and retains a singular/historic moment, which gains relevance and representativity by being captured at a particular time, his images extract the architectures from the unique moment in which they were shot and show them as belonging into a dynamic, temporal flow of time. They record the buildings as traversing different epochs.

Secondly, and as a consequence of this, his images are not preserving memory, in the sense of canning a past reality. Thinking about the traumatic last decades of colonial rule followed by a fierce war of independence, showing Luandan architecture in transformation, means overpassing the repressive determinations of this historical moment and formulates a strong critical position.

How is this technically achieved?

His images turn visible their own process of making. They remain open and show the various layers of treatment, which Delio applied upon them. Some images are for example found photos (taken some decades ago by amateurs) which Jasse photographed again in order to obtain a negative, which he prints again, as if it was an original. Other images reveal the application of the photographic emulsion, which again creates a reflexive gap in time between the subject and the support.“I do not consider my photography documentary, even if, in most cases my point of departure is a document (for example a portrait or a the photo of an existing building). Starting with this document (which I prefer to call record), I start to experiment with the means of analogue photography, process in which the record looses progressively its reality, gaining new elements. I am constantly developing an archive from the past, which to me is settled in an indefinite reality, which is nor past nor present, nor real nor false, it is in-between.”

Memory is therefore somehow undermined. And this new quality that the architectures in his work gain – of documenting/transmitting their own transformation in time, means that they are shown as intervening upon the ideological containments, which first of all determined their formal vocabulary . This is somewhat paradoxical, thinking of the paradigmatic qualities of architecture: stability, permanency, immutability.

Delio Jasse depict these buildings in relation. In relation to time – as traversing certain historic durations – but also in relation to the people, which appear in movement, always circulating, in his images. It is foremost in this relational quality of his architectures, that the political force of these images seems to reside.

Contrary to the documentary photography from the epoch, in which architectural photography is rather a de-populated, self-sufficient formal study, in Delio Jasse's images, the buildings appear in relation to the people that inhabit it – the society – reminding of the fact that architecture is a means to design opportunities for people.

In the context of colonial architecture, which represented a visual frontispiece of the Empire's ideology, adapting architecture to the exigency of the local community, understood as a powerful social body, was a political project of the above mentioned architects (Simoes de Carvalho or Vieira da Silva).

If hegemonic architecture is meant to fix historic meaning and last, the way these buildings have been adapted and altered for a non-hierarchic use by the citizen of Luanda with the add of ephemeral construction materials, points to the value of such adaptations as political counter-statements.

A definite political power resides in these slow mutations. They point to reciprocal determinacies between people and public architecture – if it is habitational or industrial. They show the way architecture determines movement, posture, the urban sense of being and how it dictates the dimensions that people can take in the city. Delio Jasse's images attest – by not fixing a certain moment in time, but by layering time and space – how the proportion of architecture in relation to the human get distorted: architectures seems oversized beside the human. They show how historic transformation is subjectively perceived, more than an objective form fixed in time.