MARTA JECU CURATORIAL TEXT

MUSEUM OVER FLOW

TADASHI KAWAMATA AT MAAT LISBON

'We are sinking. We are sinking, as individuals, as participants in a field that is sinking along with us, as members of a species, and as components in a massive, global ecological network. But we are not sinking because of the malevolence of natural forces, not because the sand is hungry for us and for our horses (...) We are not sinking because whales and monstrous fish want to swallow us whole, not because the strange beings of the sea wish harm on us, nor because the sea itself is vengeful, though “the water comes,” and who could blame it? We are sinking because of our collective hunger and callousness. As dwellers in the anthropocene, we can already see it all around us.' (Simon Mittman 2017)

Tadashi Kawamata's installation at MAAT Lisbon confines this beginning-end-beginning loop which brings on the shores of a museum the shipwrecked hybrid configuration of the perpetually returning debris of human civilisation. The world of the inanimate uncannily outlasts the human dimension.

Beaches are the paradigmatic place of mutual rejection and encounter of the human and natural dimensions, of the 'own' and the 'foreign'. A very interesting question regarding 'otherness' arises: as the seas reject pollution, the beaches deliver us back not unknown bodies from the sea's abyss, but mainly our own civilisational wretches – those which we couldn't tame and understand – our own garbage. The 'other' is not any longer the unknown natural realm, but turns to be paradoxically a mirror of our un-escapable 'self' and exposes our own ecological failures.

Tadashi Kawamata's project in MAAT is a three-fold endeavour. The installation is the consequence of years long confrontations of the artist with questions regarding ocean ecology, natural catastrophe, ecologic catastrophe, which he has explored during his career in site specific works world-wide. On the other hand the work produced in Lisbon is preceded by a thorough preoccupation for the situation found in -situ, which Kawamata has been exploring along many visits and data collection in Lisbon in the past year. The debris which flows into this installation was collected on Portugal's coast near Lisbon in 2018, during different campaigns by Brigada do Mar1 – a volunteer organisation which regularly contributes to the cleaning of the beaches of Portugal. From them we learn about a global circulation of garbage in the world's seas: what we find on the shores of Portugal is waste produced by many continents. The boats shipwrecked inside Kawamata's installation talk as well about questions related to global tourism and its fatal consumption of natural resources. Deposited in the warehouses of the town-hall of Almada, which generously supported this project, these found mountains of garbage have passed also through the laboratory of Espacialistas2 – a team of architects and researchers – who, in collaboration with Tadashi Kawamata studied the hybrid configurations that the ocean, its movements and artificial components formed progressively from the wasted fragments. Applying the principles of these fusion pieces produced by the ocean, the student workshop with Espacialistas created new modules, which the artist incorporated into his installation.

When contemplating Tadashi Kawamata's under water environment in the MAAT where the viewer does hardly know his own point of perspective – on shore or off, floating or already submerged, outdoors or in an indoors artificial environment – two questions arise:

'Which is our conscious position in relation to Nature?' and 'What is the role of the museum in this relation?'

MUSEUM AND THE SEA

The Natural History Museum was historically the site where a world that did not surrender to humanity’s desire for authority was slowly by slowly tamed. Colonial campaigns directed towards the surrender of distant cultures went hand in hand with the domestication of the seas not only by navigating and plundering them, but mostly by studying and representing them. This historically conflictual relationship between the technology of submission and knowledge formation and a perpetually sovereign and changing nature – is transported by contemporary eco-critique. It is in fact the sea itself which carries us back to our own representation of it. In Tadashi Kawamata's installation, the museum is over flown by the near-by sea, exhibiting not the remains of a scientific order constructed over centuries, but a hybrid artificial monster expelling yet unknown morphologies – forms, materialities, colours – results of atomic fusions with devastating finalities.

The idea of recurrence and over-flow – the constant return of human input as part of larger ecological movements – that Tadashi Kawamata's installation talks about, is a prominent theme in science-fiction. We can here think of Nautilus, the submarine of Captain Nemo in Jules Verne's novel Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (1870). This underwater museum in which he collects the treasures of the underworld, impersonates his critique and estrangement of his own society and its cultural values. But for Celeste Olalquiaga, Nemo's versatile and uterine museum represents at the same time the pragmatism and voyeurism of the 19th century and incarnates the project of modernity: substituting tradition with technological progress and the individual's consequent alienation (Olalquiaga 2011).

The museum installation of Tadashi Kawamata can be also seen through the prism of a long tradition of environment art and its rejection-attraction dialogue with the museum. Relevant can be in this context the terms launched by Robert Smithson: 'non-site' versus 'site', which announce and launch main concepts of ecological art. These terms describe the correspondences between in-situ action and artistic representation/documentation inside the museum space ('site'), while 'non-site' (the work inside the museum) conceptualises the problems posed by the environment. Realised between 1965 and 1969 the 'non-sites', these proto-ecological art forms, where works which condensed in an abstract form the unlimited, dispersed and un-graspable open air 'site'. Similar to Kawamta's working process, the 'non-sites' were a means of collecting material from the 'site', condensing their nature and at the same time reproducing a museological principle: taking samples and tracing their dense net of implications for the terrain and the context.

NATURE AND THE MUSEUM-LAB

Bruno Latour (Latour 2003: 38) argues that we already live in the ruins of Nature – on which we produce our future. Latour imagines our planet as an extended outdoors laboratory – the world wide lab. The experiments and the lab are spreading outside and nature goes indoors.

OVER FLOW catches this precise moment when the results of scientific modifications (reserved before to the confines of the lab or the museum) spread onto the beach and in the deep sea, while nature turns artificial and goes inside the contemporary museum.

In this same article, Bruno Latour affirms that currently we have transited from the era of science to the era of research (Latour 2003: 30):

'We have shifted from science and its modernist dream of total control, with unwanted consequences appearing only later, without ever putting the original dream of control into doubt, to research. Research is just the opposite of science, careful experiments just the opposite of total control.' (Latour 2003: 30)

And indeed the hybrid models and conglomerates which form the body of Tadashi Kawamata's installation and produced during Espacialista's experimental workshop are the product of research.

Besides its apocalyptic tones, Tadashi Kawamata's installation introduces therefore also a positive perspective.

These emerging modules – based on an investigation of the principle of natural fusion that the ocean operates in its movement – extend these principles to the creation of original pieces.

Based on both digital and analogue production, on pieces of natural and artificial materials which the sea brings back to us and which cover the surface of the sea, these newly produced hybrid forms extract from the apocalyptic products of our ecological disasters possibly functional principles.

As the modules and patterns found in the ocean and assembled in various ways in the body of this installation show, the objects represented inside 'the museum' are finally unforeseen.

The status of the museum-lab itself becomes indefinite while oriented towards scientific-artistic experiments. The nature of this new museum, based on complex variables is oriented towards the exploration of future possibilities, rather than on the museum's historic function of documenting 'the world outside'.

'Nature, contrary to superficial impression, is not an object out there but above all a political animal!: it is the way we used to define the world we have in common, the obvious existence we share, the sphere to which we all equally pertain.' (Latour 2003: 38).

As a viewer of Kawamata's installation, we re-enact a position of disaster-tourist, coming to explore the spectacularity of destroyed sites – similar to the subculture of illegal tourism around the Fukushima site. It is important to ask (beyond mere contemplation) how can a work of art activate a regenerative potential latent in the disaster depicted. OVER FLOW itself functions as an agent of memory, a record of a continuous global movement leading to erosion and destruction and a document of powerful interconnections across geography and history. The acts of colossal destruction that this installation evokes, reverberate between historic and contemporary times, between Japan and Europe for example.

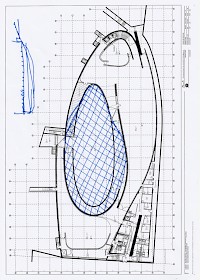

Being eco-critically positioned, but also being located in the Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology, Tadashi Kawamata's installation challenges nevertheless a dualistic perspective on nature being opposed to urbanity and opens the field towards urban ecology. In fact, MAAT bordering the river Tejo close to the point of affluence into the sea, proposes permeation. The installation represents not only what nature delivers back to the civilisation, but also a possible point of creative fusion: the point where the museum and the installation itself can transform and re-digest the status quo, proposing new and counter-hegemonic solutions.

As Kawamata's installation is the result of a confluence of actions by militant and eco-active groups (Brigada do Mar) and a long tradition of collective ecologically aware efforts in Portugal, it gives continuation to ecologically oriented examinations (Espacialistas), counter-acting loss and the strangeness of our encounter with artificial and prosthetic extensions of nature – with creativity and agency.

How to represent the ocean – a body in perpetual movement, fundamentally unknown to humans? Tadashi Kawamata's work and working process chooses to represent it as a mirror of our own social and political condition – in a long cultural tradition that formed itself with medieval maritime monsters that were incarnations of social sins and fears or Nemo's futuristic Nautilus-museum.... When being immersed in Tadashi Kawamata's installation we are physically confronted with what we have made of nature, but our reflection in it remains continuously distorted – as we find ourselves involved in collective experiments that we are only partially aware of.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Asa Simon Mittman and Thea Tomaini (2017): Sea Monsters: Things from the Sea, volume 2, Tiny collections, Punctum Books.

Tadashi Kawamata (2017), Informal discussion 18 October 2017, Paris.

Tadashi Kawamata and Guy Tortosa (2013), Interview – Kawamata: The Metabolism of the World, Kamel Mennour Edition, Paris.

Bruno Latour, Atmosphere, atmosphere, in Susan May (ed.) 2003, 'Exhibition catalog of Olafur Eliasson', at New Tate, 2003, New Tate, London, pp. 29-42.

Celeste Olalquiaga, L'Homme Meuble, in 'Oceanomania, Souvenirs des Mers Mysterieuses', Nouveau Musee National de Monaco, Monaco 2011, pp. 36-43

1

http://www.brigadadomar.org/

2 http://www.osespacialistas.com/

THE EXHBITION OF TADASHI KAWAMTA INCLUDES SEA DEBRIS COLLECTED ON THE PORTUGUESE SHORES IN ECOLOGICAL ACTIONS BY VOLUNTEERS ORGANISATIONS.

Quantity of total debris collected by the end of campaigns: 700 m2 debris

ACTIONS - BRIGADA DO MAR BEACH CLEANINGS 2018

==5-13 May 2018, Place: Troia to Melides, about 45km of beach cleaning - https://goo.gl/maps/bjafhgYSuzo

Limpeza de Praias da Costa de Grândola, 10.ª Edição / Cleaning of the Beaches of the Coast of Grândola, 10th Edition – 2018, Brigada do Mar.

Organizer and promoter: Brigada do Mar, IMAGES: Tworlds Productions

Number of participants: 400 from 6 different nationalities

Materials collected: fishing objects, plastic objects, ropes, barrels (most of times containing corrosive liquids and oils), medical utensils and medicines, lamps, glass and plastic bottles, electrical appliances etc.

Context: every May in the past 10 years Brigada do Mar brought together volunteers from Portugal and the rest of Europe for 15 days beach cleaning campaigns between Troia and Melides. Sado Estuary Nature Reserve, Santo Andre and Sancha Lagoons Natural Reserve are areas of sandy beaches and natural reserves, classified as natural heritage by different national and international organisms. They are populated among other species by a colony of bottlenose dolphins. Statement provided by Brigada do Mar to the press imder https://ionline.sapo.pt/artigo/615473/associacao-apanha-26-toneladas-de-lixo-em-45-km-de-costa?seccao=Portugal_i#disqus_thread

==Date (1 April – 31 May 2018 : Place: Cova do Vapor to Fonte da Telha, about 19km - https://goo.gl/maps/Mqw3skdsrW52

Organizer and promoter: Câmara Municipal de Almada/City Council of Almada.

Number of participants: team of 6 people, 2 tractors and 1 trailer

Material: during the spring season the debris arrives with tides and with the Tejo river from industry, shipping and commercial fishing. In summer the waste is left by the beach users.

During the beach season, the cleanup activities happen every day. At night, the sand cleanup is done with specific beach cleaning machines and in the morning by the municipal workers. Around 900 waste contenders are placed on the beaches.

==Date (?): 11 June 2018 Salinas do Samouco - about 2 km - https://goo.gl/maps/C86UX3raRUr

Organizer and promoter: Brigada do Mar

Number of participants: 240 students

Material: plastic objects, glass and plastic bottles, etc.

ACTIONS – COLLECTION OF DEBRIS IN ALMADA

For the exhibition, the teams of the City Council of Almada collected debris from other organizations that had made cleaning actions in the city: Federação Portuguesa de Naturismo; Projetos Oceanos – biodegradação - colégio Nossa Senhora da Conceição da Casa Pia de Lisboa; Agrupamento Anselmo de Andrade, in the contexto of the program “Eco Escolas”; Divisão de Juventude da Câmara Municipal de Almada; Old School Surf School; Surfrider Foundation Lisboa.

ACTIONS – DEBRIS PRESELECTION FOR THE EXHIBITION

== 26 MAY – pre-selection of materials Almada Municipal Workyard with volunteers from the association Brigada do Mar. IMAGES: MATERIALS PRESELCTION WITH BRIGADA DO MAR , 26 MAY

Material: 200 m2 of big objects on a beach area of 65km.

30 June: debris preselection in Almada Municipal Workyard: IMAGE 100m2_Junho 2018'

Material: 100m2 of big objects on a beach area of 65km

==Date July 2018 Preselection of debris accumulated in Nazaré Port (IMAGES PORTO NAZARE). The debris will be transfer to Lisnave (Lisbon) after the preselection

PROJECT PARTNERS

==Almada City Council – offered one of their municipal workyards for the storage and cleaning of the collected debris for the exhibition. They are also responsible for the cleaning of these large amounts of debris. In September a professional team will build at Lisnave, Cacilhas, Almada (http://www.lisnave.pt/company.htm)

the modules designed during the worshop with the Espacialistas architects team.

ACTIVITIES: April – August debris collecting and material selection support

==Os Espacialistas Architects Team (http://www.osespacialistas.com/)– design of debris modules to be integrated into Tadashi Kawamata's installation. Collaboration with architecture students under the supervision of the artist.

Estimated nr of modules needed: 300.

ACTIVITIES: 28th - 31st August workshop

==Brigada do Mar (http://www.brigadadomar.org/): volunteer organization responsible for regular beach cleaning campaigns on the Portuguese coastline. They selected and offered collected debris to be included in the installation and accompanied the entire project.

ACTIVITIES: April – August debris collecting from Almada (north) to Sines (south).

==Grândola City Council – offered the transportation from Grândola to Almada of the debris collected during the Cleaning of the Beaches of the Coast of Grândola, 10th Edition – 2018 by Brigada do Mar

OTHER PROJECT PARTNERS

-Portuguese Marine and the Portugal Fishing Ports association,

- Marinha Portuguesa

Porto da Nazaré, Docapesca – Portos e Lotas, SA

Câmara Municipal de Alcochete

EXHIBITION CATALOGUE

ISSUED BY GALLERY KAMEL MENNOUR PARIS

2017

‘We are sinking. We are sinking, as individuals, as participants in a field that is sinking along with us, as members of a species, and as components in a massive, global ecological network. But we are not sinking because of the malevolence of natural forces, not because the sand is hungry for us and for our horses [...] We are not sinking because whales and monstrous fish want to swallow us whole, not because the strange beings of the sea

wish harm on us, nor because the sea itself is vengeful, though “the water comes”, and who could blame it? We are sinking because of our collective hunger and callousness. As dwellers in the anthropocene, we can already see it all around us.’ (Simon Mittman 2017)

Tadashi Kawamata’s installation at MAAT Lisbon confines this beginning-end-beginning loop which brings to the shores of a museum the shipwrecked hybrid configuration of the perpetually returning debris of human civilisation. The world of the inanimate uncannily outlasts the human dimension.

Beaches are the paradigmatic place of mutual rejection and encounter between the human

and the natural, between what ‘belongs’ to us and what is ‘foreign’. A very interesting question regarding ‘otherness’ arises: as the seas reject pollution, the beaches deliver back to us not unknown bodies from the seas’ abyss, but mainly what our our own civilisation'S wreckage , what we couldn’t tame or understand: our own garbage. The ‘other’ is no longer the unknown natural realm, but paradoxically turns out to be a mirror of our inescapable ‘self’ and exposes our own ecological failures.

Tadashi Kawamata’s project at MAAT is a three-fold endeavour. The installation is the consequence of years of the artist’s investigations into questions regarding ocean ecology, natural catastrophe, and ecological catastrophe, all of which he has explored during his career in site specific works around the world. On the other hand, the work produced in Lisbon is preceded by a thorough engagement with the found, site-specific situation, which Kawamata has been exploring over the course of many visits and data collections in Lisbon in the past year. The debris which flows into this installation was collected on the coast near Lisbon in 2018, as a part of a series of campaigns conducted by Brigada do Mar–a volunteer organisation which regularly contributes to the cleaning of the beaches of Portugal. From them we learn about a global circulation of garbage in the world’s seas: what we find on the shores of Portugal is waste produced by many continents. The boats shipwrecked inside Kawamata’s installation also speak to questions related to global tourism and its fatal consumption of natural resources. Deposited in the warehouses of the town hall of Almada, which generously supported this project, these found mountains of garbage have also passed through the Espacialistas laboratory, a team of architects and researchers who, in collaboration with Tadashi Kawamata, studied the hybrid configurations that the ocean, its movements and artificial components progressively formed from the waste fragments. Applying principles found in these fusion pieces produced by the ocean, a student workshop and Espacialistas created new modules, which the artist incorporated into his installation.

When contemplating Tadashi Kawamata’s underwater environment at MAAT, where the viewer hardly knows his own point of view–on shore or off, floating or already submerged, outdoors or in an artificial indoor environment–two questions arise: ‘What is our conscious position in relation to Nature?’ and ‘What is the role of the museum in this relationship?’

The MUSEUM AND THE SEA

The Natural History Museum was historically the site where a world that did not surrender to humanity’s desire for authority was slowly tamed. Colonial campaigns directed towards the surrender of distant cultures went hand in hand with the domestication

of the seas not only by navigating and plundering them, but mostly by studying and representing them. This historically conflictual relationship between the technology of submission and knowledge formation and a perpetually sovereign and changing nature is the object of contemporary eco-critique. It is in fact the sea itself which carries us back to our own representation of it. In Tadashi Kawamata’s installation, the near-by sea overflows the museum, exhibiting not the remains of a scientific order constructed over centuries, but a hybrid artificial monster expelling as yet unknown morphologies–forms, materialities, colours–the products of atomic fusions with devastating finalities.

The idea of recurrence and overflow–the constant return of human input as part of larger ecological movements–that Tadashi Kawamata’s installation speaks about is a prominent theme in science-fiction. One could here think of Nautilus, Captain Nemo’s submarine in Jules Verne’s novel Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (1870). This underwater museum in which the treasures of the underworld are collected figures Verne’s critique and estrangement of his own society and its cultural values. But for Celeste Olalquiaga, Nemo’s versatile and uterine museum represents at the same time the pragmatism and voyeurism of the 19th century and embodies the project of modernity: substituting tradition with technological progress, with the individual’s consequent alienation (Olalquiaga 2011).

The museum installation of Tadashi Kawamata can be also seen through the prism of a long tradition of land art and the dialogue of rejection-attraction that it maintained with the museum as an institution. Robert Smithson’s terms would be relevant in this context, in particular his notion of ‘non-site’ versus ‘site’, which were foundational for the conceptual coordinates of ecological art. The terms describe the correspondences between site-specific action and artistic representation/ documentation inside the museum space (‘site’), while ‘non-site’ (the work inside the museum) conceptualises the problems posed by the environment. Realised between 1965 and 1969, the ‘non-sites’, these proto-ecological art forms, where works which condensed in an abstract form the unlimited, dispersed and un-graspable open air ‘site’. Similar to Kawamata’s working process, the ‘non-sites’ were a means of collecting material from the ‘site’, condensing their nature and at the same time reproducing a museological principle: taking samples and tracing their dense net of implications for the terrain and the context.

NATURE AND THE MUSEUM−LAB

Bruno Latour (Latour 2003: 38) argues that we already live in the ruins of Nature– on which we produce our future. Latour imagines our planet as an extended outdoors laboratory–the world wide lab. The experiments and the lab are spreading outside and nature goes indoors.

OVER FLOW catches this precise moment when the results of scientific modifications (previously reserved to the confines of the lab or the museum) spread onto the beach and in the deep sea, while nature turns artificial and goes inside the contemporary museum.

In the same article, Latour affirms that we have currently transited from the era of science to the era of research (Latour 2003: 30):

‘We have shifted from science and its modernist dream of total control, with unwanted consequences appearing only later, without ever putting the original dream of control into doubt, to research. Research

is just the opposite of science, careful experiments just the opposite of total control.’ (Latour 2003: 30)

And indeed the hybrid models and conglomerates which form the body of Tadashi Kawamata’s installation and produced during Espacialista’s experimental workshop are the product of research. Besides its apocalyptic tones, Tadashi Kawamata’s installation thus also introduces a positive perspective.

These emerging modules–based on an investigation into the principle of natural fusion that the ocean conducts in its movement–extend these principles to the creation of original pieces.

Based on both digital and analogue production, on pieces of natural and artificial materials which the sea brings back to us and which cover the surface of the sea, these newly produced hybrid forms extract from the apocalyptic products of our ecological disasters possibly functional principles.

As the modules and patterns found in the ocean and assembled in various ways in the body of this installation show, the objects represented inside ‘the museum’ are ultimately unforeseen.

The status of the museum-lab itself becomes indefinite while oriented towards scientific-artistic experiments. The nature of this new museum, based on complex variables, is oriented towards the exploration of future possibilities, rather than the museum’s historic function of documenting ‘the world outside’.

‘Nature, contrary to superficial impression, is not an object out there but above all a political animal!: it is the way we used to define the world we have in common, the obvious existence we share, the sphere to which we all equally pertain.’ (Latour 2003: 38).

As a viewer of Kawamata’s installation, we re-enact a position of disaster-tourist, coming to explore the spectacularity of destroyed sites–similar to the subculture of illegal tourism around the Fukushima site. It is important to ask (beyond mere contemplation) how can a work of art activate a regenerative potential latent in the disaster depicted. OVER FLOW itself functions as an agent of memory, a record of a continuous global movement leading to erosion and destruction and a document of powerful interconnections across geography and history. The acts of colossal destruction that this installation evokes reverberate between historic and contemporary times, between Japan and Europe for example.

Being eco-critically positioned, but also being located in the Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology, Tadashi Kawamata’s installation challenges nevertheless a dualistic perspective on nature being opposed to urbanity and opens the field towards urban ecology. In fact, MAAT, which borders the river Tejo close to where it spills into the sea, proposes permeation. The installation represents not only what nature delivers back to civilisation, but also a possible point of creative fusion: the point where the museum and the installation itself can transform and re-digest the status quo, proposing new and counter-hegemonic solutions.

Just as Kawamata’s installation is the result of a confluence of actions by militant and eco-active groups (Brigada do Mar) and a long tradition of collective ecologically aware efforts in Portugal, it gives continuation to ecologically oriented examinations (Espacialistas), counter-acting loss and the strangeness of our encounter with artificial and prosthetic extensions of nature–with creativity and agency.

How to represent the ocean–a body in perpetual movement, fundamentally unknown to humans? Tadashi Kawamata’s work and working process chooses to represent it as a mirror of our own social and political condition–in a long cultural tradition that stretches from the medieval maritime monsters that were incarnations of social sins and fears through Nemo’s futuristic Nautilus-museum.... When being immersed in Tadashi Kawamata’s installation we are physically confronted with what we have made of nature, but our reflection in it remains continuously distorted–as we find ourselves involved in collective experiments that we are only partially aware of.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

• Asa Simon Mittman and Thea Tomaini (2017): Sea Monsters: Things from the Sea, volume 2, Tiny collections, Punctum Books.

• Tadashi Kawamata (2017), Informal discussion 18 October 2017, Paris.

• Tadashi Kawamata and Guy Tortosa (2013), Interview – Kawamata: The Metabolism of the World, Edition kamel mennour, Paris.

• Bruno Latour, Atmosphere, atmosphere, in Susan May (ed.) 2003, ‘Exhibition catalog of Olafur Eliasson’, at New Tate, 2003, New Tate, London, pp. 29-42.

• Celeste Olalquiaga, L’Homme Meuble, in ‘Oceanomania, Souvenirs des Mers Mysterieuses’, Nouveau Musée National de Monaco, Monaco, 2011, pp. 36-43.

www.brigadadomar.org

www.osespacialistas.com