‘If it is an invention, I am not able to know it’

‘Actually, I don’t know what I am, because if it is an invention, I am not able to know it,’ confessed in the Seventies artist Helio Oiticica, in his Parangolé peregrinations starting in Brasil and reaching New York.i The New York subway witnessed his explosive visions and living sculptures, while he appropriated the new environment with movement and colour, generating a continuous space across continents and cultural conventions. This was maybe the beginning of a new fluidity in connecting distant spaces through the experience of a reinvented self, surfaced in the freedom of simultaneous experiences in different geographies, without subordinating the environment to a predetermined cultural discourse.

It becomes necessary to ask: how are distant spaces reached for, how how do objects move in space and how do things or people change while in different spaces? How do things start to look alike when they share the same space? How is social and political territory demarcated and in which ways can movement create new possibilities for the individual’s position in relation to these demarcations?

Recalling Oiticica’s experiments with Parangolé, the photographer Thabiso Sekgala invents connections between distant places, which make real the possibility of a new dimension of the self. In his collection of images for Peregrinate, first shown at the Goethe-Institut in Johannesburg, connecting his work to that of the photographers Mimi Cherono Ng’ok and Musa Nxumalo, Sekgala works with combined series of images. Not only in this current exhibition, but also in previous shows, he juxtaposes images that he has shot during his travels or at home that apparently have no spatial and temporal affinity: images from South Africa mixed with images from Germany or Jordan. These disparate insights installed in series, one beside the other, create a new continuity in space that surmounts the all-too-frequent distinctions between European/African and non-European/African spatial characteristics.

At the same time, a mode of photography oriented towards delimiting hypostasis in space and time is opened up. As places get connected in space, time also is rendered non-chronological and the self is released from temporal restrictions: the time after leaving homeland or the time before arriving in the new place.

Talking about the reciprocal determinations between place and culture, Sekgala poses the problem of photography’s own means of showing spatial continuity in movement, paradoxical to the medium’s apparent static means of representation. ‘When you are photographing places – for example, traveling by bus – there is a kind of ordering of places. But you cannot really order places. When you say, “this is my place, my country”, how do you own it, how do you differentiate it? My work is about people moving out from one place into another place. A place is just an open, natural place; it is we who put things into it.’ii

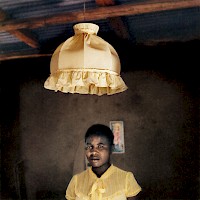

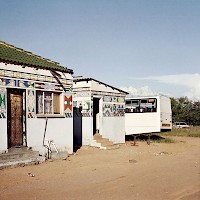

Individual frames record people standing in their surroundings, isolated from the daily activities in which they are probably entangled – constructions immersed in a landscape without time, inert objects without any particular identity, thrown away. Seen in this way, they recall ethnographic photography’s specific way of setting a still subject in the studio, which then started to be also shown in an environment, where it was presented as being representative for an entire context. Nevertheless, Sekgala does not consider his work as being documentary: ‘My work does not have the quality of current affairs.’

In Sekgala’s mix of images from Zimbabwe, Germany, South Africa, among other places, the pattern established by the journalistic tradition of South African photography is filled with different content. It is actually the migratory gaze that determines the nature of the image – treating the individual and the landscape in the same way, without psychological, aesthetic or ethnographic appreciation. In the mixed series of images, the intention comes through to look simultaneously at people and places from Berlin in the ways that he looks at his home-places in South Africa, and this particular cinematic gaze merges the distant places together.

Contrary to ethnographic photography, but also to journalistic photography, where the gaze searches for untried experiences, the spectacular and the new to feed curiosity, in Sekgala’s geographic juxtaposition of images, a slow continuous time and space unifies cities, places, people. It emanates from a type of inclusive perception, in which the traveler knows his unfulfillable condition. The searched-for places can actually never be reached. This is, at the same time, the contemporary condition of the traveler, that Zygmunt Bauman described with the beautiful idea of ‘liquid modernity’. Contrary to the ‘solid modernity’ of the 1960–1980 era in which the practice of traveling was based on distinctions between home and away, work and leisure, authentic and staged, the contemporary liquid way to be and to move in space is less determinant and also less expectant.

Talking about traveling today in an interview with Adrian Franklin, Zygmunt Bauman says it is: ‘To be always ready for another run – this is the name of the game.’iii This was also the subject matter of a previous exhibition by Sekgala, Running, that took place at Goodman Gallery in Cape Town earlier this year, and had at its core lyrics by Gil Scott-Heron, which describe running as the expression of the contemporary soul:

Because I always feel like running, not away, because there is no such place

Because, if there was I would have found it by now

Because it’s easier to run, easier than staying and finding out

you’re the only one who didn’t run.

Because running will be the way your life and mine will be described,

As “in the long run” or as in having given someone a “run for his money”

Or as in “running out of time”

Because running makes me look like everyone else;

though I hope there will never be cause for that

Because I will be running in the other direction, not running for cover

Because if I knew where cover was, I would stay there and never have to run

for it…

Tourism searches for substitutes that make the real thing even more absent, as instant cures for the traveler’s saturated eye.iv But in Sekgala’s images, traveling has a deeper tone, which carries in it distorted reflections of migration with its complex policies of movement. Not the same as traveling by choice, migration is a negotiation of cultural and political space, and an always not successful settling. Bauman calls the migrant a ‘vagabond’, since he is coerced by society to have no place of his own and to be restlessly unable to build a solid relationship with his environment. ‘In our liquid–modern world you need not move an inch to turn into a vagabond. You are still in the same place, but the place is no longer what it was,’ he says.v

The travels of the migrant-vagabond take place in a ‘no-where’ zone, composed of both rooted and delusive sites. It is a constant peregrination in a conceptual zone, rather than in a territory with a reachable physical identity; a dissident mix of desires and a confrontation with political constraints. Nevertheless, in Sekgala’s images the camera faces the cultural reality in front of it in a direct, unpretentious way, eliminating spectacular details or the exotic. His proximity to the photographed object has a familiar feeling about it, that acknowledges at the same time the impenetrability of the others and the hermetism of personal experience.

Awareness of restricted freedom of movement connected to transnational circulation and migration policy (that the photographer and a a large majority experience), shapes the cultural presence of the places observed through his images. EU immigration policies have transformed the Mediterranean into a border to inland African countries, controlled on one side only by the EU, which restricts the freedom of movement in both directions. Still, migrant workers, leisure or cultural travellers move mentally through more than one geographical territory. This new type of mobility with its specific mental geography shapes one’s own subjective identity, but at the same time has the power to determine change and actively move political boundaries.

"I photograph these places as if nothing has happened, but also as if something has happened to them. This is my way of looking at them. I did not want to follow a certain narrative or topic; it’s a combination of images of different places joined together. In Soweto, people were forced to settle, but over time, they have made this place their own, so they’ve become this place that has its own identity. This is not a place that was their own, but they made it to be. When you say Soweto, you think about a certain identity.’

Coming close to places on the level of representation augments their seduction, and in these images a sort of diffuse longing comes through. But the images of these places are not there to build memories, or to assign exceptional past moments meant to last in time. Rather, they can be regarded as setting a dialogue with boundaries. Contemporary movement is defined by the traveler's simultaneous being in and absenting from the various places he traverses. Sekgala’s quiet images of distant-to-each-other places, joined in the same space of representation (in a series or on the exhibition wall), recall the condition of the contemporary peregrine; that is an active negotiator of borders. Trespassing that which is conventionally not be mixed, has always had a liberating charm to it.